By Michael Karam

Château Ksara was established in 1857, after Jesuit monks inherited a 25-hectare plot of land situated between Tanail and Zahle in the Bekaa Valley, and began planting Cinsault, Carignan and Grenache grape varieties brought from Algeria. In doing so, they laid the foundations for the modern Lebanese industry. For the next 116 years – through two World Wars, the end of the Ottoman Empire, the French Mandate and Independence – the Jesuits were at the forefront of the Lebanese wine industry. In 1973, after a papal decree forced the Jesuits to sell the winery to the Lebanese private sector, the winery’s new owners ensured that Chateau Ksara remains solidly connected with the Jesuit tradition in Lebanon and the history of the country itself.

The ruined Baalbek temple of Bacchus in the late 19th century before it was restored. Norbert Schiller Collection, phot. Bonfils

Brother Mold, a Jesuit who arrived in the Bekaa in 1892, makes the following observations in his journal: “The Bekaa is known as La Creuse de Syrie. It is surrounded by huge mountains and a valley 25 leagues in length and 4 leagues across. Baalbek and Chalcis are the most important cities, although their period of glory is over and they now lie in ruins.”

He continues: “Nowhere in the world is there such an abundance of water. The springs, the biggest of which is the Litani, are so powerful the locals call them rivers. The swamp at Tanail is full of pelicans, geese and ducks, and in the summer it is the place where the Bedouin feed their herds.” Then a darker note: “Due to the fighting of 1860, five of our own [priests] fell in the disturbances.” He goes on to lament that the Turks have completely mismanaged the area and have not taken advantage of its fertility and notes that many of the locals are leaving because of the dire economic situation.

The tomb of the prophet Noah in the village of Kerak near Chateau Ksara. Noah is considered to be the first vigneron. Phot. Norbert Schiller

However, there is a bright spot in his often-bleak observations. “At the vineyard named after St. Alphonse, who has just been canonized by the Pope, the vines are esteemed … It is close to the village of Kerak, where there is a tomb to the Nabi Noah, who was a vigneron of note.”

The vines he mentions were part of a vinicultural tradition that began 35 years earlier in 1857, when, according to Father Michel Jullien’s modest essay, The New Jesuit Mission in Syria 1831-1895, Jesuit monks inherited and began farming a 25 hectare plot of land situated between Tanail and Zahleh. The land was a gift from one Father Rousseau, who, like Mold, had been impressed by area’s abundance of water and its Roman antiquities. Jullien tells us that Rousseau believed the name Ksara to be derived from the Arabic qaisarieh or Caesarea (although another equally plausible theory suggests that the area got its name because it was the site of a Crusader ksar, or fortress).

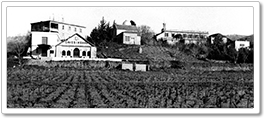

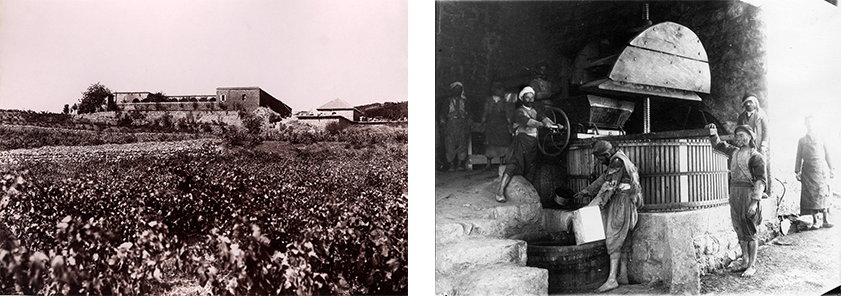

The grape vines leading up to the main building where the Jesuit monks had their winepress and a small chapel. Today the building is the main reception area for Chateau Ksara. Phot. Tanail Jesuit Monastery Collection

It was a resident priest, Father Kirn, who recognized the potential of Ksara’s terroir and convinced the other priests that it should be used to grow grapes for viniculture. This would not have posed a problem under the Islamic Ottoman rule: the monks of Lebanon were already making sweet wine, or vin doux, with the permission of their Turkish masters, provided it was only used for religious purposes. In fact, the Ottomans tended to look the other way when it came to alcohol. Arak, Lebanon’s aniseed liqueur, similar to the Turkish Raki, was widely drunk and acquired a reputation that spread throughout the Middle East.

The exact motives of these pious pioneers remain unclear, but Kirn and his fellow monks, possessing a solid education in agriculture and the sciences, applied what they knew and set out to produce Lebanon’s first “dry” red wine. In doing so, they began to lay the foundations of the modern Lebanese wine industry.

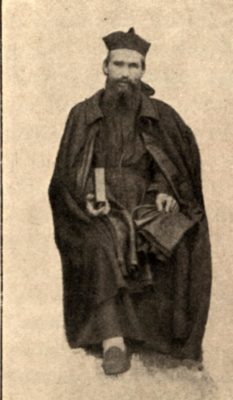

Father Andre Kirn

The introduction of new grapes

Kirn, who went on to become head of the monastery in 1881, knew this “revolution” would need new vines. In 1878, he appointed a trained viticulturalist, Father Francois Wuillamoz, who, with his assistants, Fathers Jacob Dorsch and George Winlen, lent more technical expertise to the mission’s winemaking initiative. They decided to import what was then considered “les meilleurs cepages” from Algeria, the most important of France’s colonial wine-producing territories.

Wuillamoz, who had traveled with Kirn from Boufarik, an important grape-growing area in Algeria, knew that if he were to get the results he wanted, he had to plant new vines. His consignment of vines, understood to have been either Cinsault or Grenache, reached Lebanon shortly before the Ottomans imposed a ban on imported foreign plants, due to the spread of Phylloxera, the dreaded vine disease caused by aphids that wiped out most of the Europe’s vines in the nineteenth century.

Vin D’Or, the first Lebanese wine to travel abroad

The results were so successful that Mold declared his wine to “possess more bouquet than any in the whole of Syria, the most esteemed being the Vin D’Or.” Brother D’Ore also waxes lyrical: “What wonderful wines! They are sent abroad to be used in church services in Bavaria, Prussia, Holland and the countries of the Far East,” while Jullien writes: “Today the domain is an excellent vineyard.” He observes that “people revel without fear of the new grapes. They know they give superior wine.”

He was not wrong. By the end of the 19th century, the Frenchman, Gerard de Nerval, one of dozens of illustrious travelers in Middle East, mentions in his travel diary “Voyage en Orient” the monastery, the underground caves and specifically the famous Vin d’Or. “The prince, having offered refreshments to his companions and myself, entered that small part of the house specially set aside for women; when dinner was served, he had with us a glass of the golden wine.”

Ksara goes it alone

In 1887, Father Kirn, the visionary of Ksara’s wine revolution, died. His successor, Father Bernardet, oversaw the move that led the Ksara property to become an independent entity of the nearby Tanail monastery. To mark the occasion, a small church was built and dedicated to the Jesuit missionary and saint, Alphonse Rodriguez, after whom Clos St. Alphonse, one of Ksara’s most famous table wines was named. Today, this church has been restored, and mass is celebrated there every Sunday.

A small chapel built next to the winery continues to hold mass every Sunday. Phot. Norbert Schiller

For many years, it was felt there was no need to have living quarters at Ksara, but there were problems with this arrangement: the monks had to walk for several hours to get to the vineyards after mass and they lost time, especially in the harsh winter. Eventually, rooms and a chapel were built and the property became more developed.

The Roman grotto is found and the observatory is built

1898 brought another milestone in Ksara’s history. A grotto dating back to the Roman era was unearthed (today, the caves run for two kilometers under the winery and form part of Chateau Ksara’s cellar system). Local orphans, engaged to work on the estate, discovered it. One of them, Jean Gharios (who went on to became a monk at the monastery until his death in 1976 at the age of 94), writes in his diary in March 1898, “The winter is exceptionally cold and long. We could not work the vineyard and, having nothing to do, we were allowed by Brother Guichard to look for the fabled grotto that we knew existed.” However, Gharios and his friends found the caves by accident rather than by detective work. Attempts to smoke out a fox that had been terrorizing chickens led the determined boys to stumble across the ancient caves.

The two kilometer network of Roman caves found below the winery provide the ideal temperature and hygrometry throughout the year for storing and aging wine in both bottles and oak barrels. Phot. Norbert Schiller

Until then, good cellars had been hard to come by. D’Ore writes that in 1895, after traveling to Palestine, Brother Michel Jullien tells the priests that “the Jews in the wineries of Richon-le-Zion are doing very well in making wine cellars but they are spending a lot of money to do this.” When it became apparent that the Roman caves were ideal for keeping wine at the correct temperature, he basked in the priests’ good fortune. “We succeeded in spending a few thousand Francs [to forge the tunnels], while the Jews of Palestine have spent a fortune.”

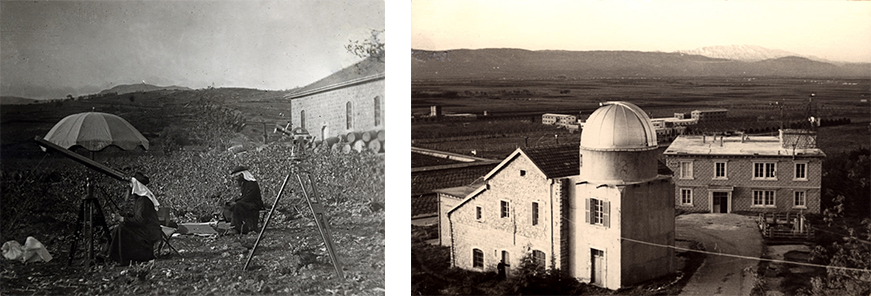

Jesuit monks at Ksara observe the passage of Mercury near the sun in 1907 (L). The observatory in the 1950s with a snow-capped Mount Hermon in the background. Phot. Tanail Jesuit Monastery Collection

In 1902, the Middle East’s first observatory was established at Ksara by the ever-curious Jesuits who wanted to record rainfall and seismic activity. The building, which was to become a strategic Bekaa landmark in peace as well as war, would become the second Ksara landmark to have a wine, L’Observatoire, named in its honor. Jesuits maintained the observatory until 1978 when it was handed over to the Lebanese government, which was unable to prevent wartime fire damage and the unfortunate theft of the telescope. Today it is a private home on the Ksara estate.

France and the Mandate

The end of World War I saw Turkey’s former imperial dominions entrusted to the victorious European powers. France was mandated to govern Lebanon and before long, its military and administrative machine moved in, bringing with it thousands of French soldiers and civil servants for whom wine was an integral part of their diet. Ksara found itself in a position to supply Lebanon’s new landlords.

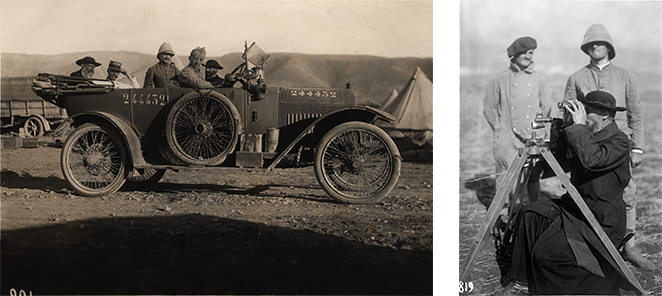

Jesuit Fathers Berloty and Combier traveling with French army surveyors in the Bekaa Valley (L). Father Berloty surveying. Phot. Tanail Jesuit Monastery Collection

By now, the winery had become a commercial concern. The monks had expanded their range of grapes with Carignan, Muscat and Ugni Blanc, and the period was one of unprecedented growth for Lebanon cottage industry winemakers in the Bekaa. From Jdita to Ryak, the French encouraged the locals to increase the production levels and to move away from making the traditional sweet raisin-based wine to making wine the French would want to drink. However, continuity was by no means guaranteed. The 1943 defeat of the pro-Nazi Vichy regime may have led to Lebanon’s independence, but the winemaking monks of Ksara feared that the departure of the French would see a drop in demand for their wine.

Father Paul Bowers(L) with the late Father Jaques Plassard at the Jesuit monetary at Tanail. Plassard worked at the winery until it was sold in 1973. Phot. Norbert Schiller

“You must remember that our early wine was not sold. It was made for the consumption of the monks. It was the French who inspired the business aspect,” says Jesuit Father Paul Browers, whose relationship with the winery stretches back to the early 1960s. “The synergy between the French army and the French Jesuits had become crucial. We thought it was over when the French left.”

Their fears were unfounded. The colonial infrastructure may have been dismantled, but the spirit remained. Lebanon had embraced the French experience and French culture with a passion that can be felt today. Wine may have still lagged behind Arak, but its embodiment of all that was France was enough to sustain demand.

The Ksara winery and observatory just prior to WWII. Phot. Tanail Jesuit Monastery Collection

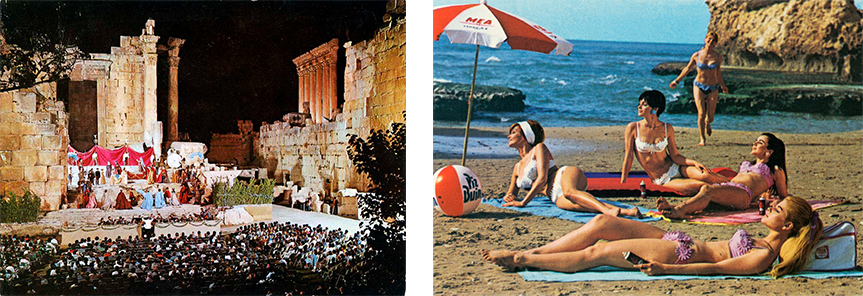

The French civil and military administration that governed Lebanon between the wars created unprecedented demand for wine. The role of post-independent Lebanon as a cosmopolitan and financial regional hub saw the country enter something of a golden age that offered further opportunities for new wine culture to take hold. Lebanon was entering a period of rare optimism and openness. It had not yoked its fortunes to those of the Arab world, and much of the Ottoman diaspora – as well as many Palestinians and Egyptians, escaping the upheaval and political tension in their own countries – sought out Lebanon’s cosmopolitan sanctuary. It had been virtually untouched by war and was ready to take advantage of the peace. This boom period lasted until 1975,

The end of the Jesuit era

Between 1946 and 1975, when the country descended into a 15-year civil war that stunted all economic development, Château Ksara maintained its position as Lebanon’s most popular wine, as Lebanon grew into a convivial hub, an oasis in a turbulent region.

Lebanon’s image of being a cultural hub and tourist destination all but died with the beginning of the civil war in 1975. Norbert Schiller Collection, Phot. (L) Manoug (R) MEA

But all good things must come to an end. In 1973, the Vatican encouraged its monasteries and missions around the world to sell off any commercial assets. By then, Ksara was producing 1.5 million bottles annually, turning Father Kirn’s vision of pastoral viniculture into a considerable corporate concern. But by now, the monks’ success was now deemed to be at odds with their religious remit.

Clergy and civilians mingle and drink wine at a Ksara reception supporting the Rights of the Child in 1963. Ultimately it was Ksara’s commercial success that forced the Vatican to sell off its interests in the winery. Phot. Tanail Jesuit Monastery Collection

Father Paul Browers remembers the period leading up to the sale. “The Vatican had to intervene and tell us that we had simply become too commercial. So we decided to sell. People thought we were mad. In 1972, we represented 85% of Lebanon’s production.”

However, the sale caused much anxiety among the Jesuits. Yes, the decision had come from Rome and yes, they accepted that it was a fait accompli, but the Ksara spirit coursed deeply through the Jesuit veins. Father Duplay, who had overseen the winery for over 30 years, was said to have wept the day it was sold. “He was the big presence in the Bekaa in terms of grapes and wine,” says Browers.

Duplay stayed with his grapes. He oversaw the vineyards at Tanail, which had a contract to supply the winery with grapes from their 100-hectare vineyards. However, he died soon afterwards in a tragic accident involving a hunting rifle that he had left loaded in his room at the monastery.

Duplay’s legacy endures to this day. Jean-Pierre Sara, the new general manager, took it upon himself to name each fermentation tank after former winery managers. “We inscribed the names of those winemakers who had gone before, so you had Duplay 1 and Cremona 3 and so on. I felt it was a fitting tribute,” he said.

Chateau Ksara today alongside a view from the early 1960s. Phot. (L) Norbert Schiller, (R)Tanail Jesuit Monastery Collection

The Lebanese papers were asking why the Jesuits were selling and even though they conducted themselves with dignity, the occasion was tinged with sadness. It is a sentiment that was echoed by Father Browers. “It is important to remember that until the winery was sold in 1973, Ksara was more than just a winery. Yes, it made Lebanon’s most popular wine, but it was also a parish, a farm, a scientific observatory – the only one in the Middle East – and a retreat. It was the physical embodiment of the Jesuit ethos. The Society has always insisted on having an area that serves as a retreat for its members. In Beirut, we had the Jesuit Gardens or Jneinet il Jesuieh, and in Zahleh, we had Ksara.”