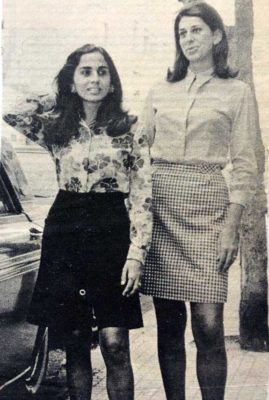

Nayla (R) and her friend Zalpha featured in a 1968 newspaper ad for a women’s clothing shop, modeling the latest fashions on Hamra Street.

“Oh to live the 60s in Beirut again! It was a time of prosperity and peace; it was a time of fun and laughter. I was young and carefree and remember the era as being by far one of the happiest times of my life!

I was born in Beirut and consider myself a Ras Beiruti. Hamra Street, grew and developed as we did: movie theaters, boutiques and fun street cafes crowned by “The Horseshoe,” where we as university students, proudly mixed with the Lebanese intelligentsia.

Politics as always in Lebanon were prevalent but did not impact our immediate everyday life as they do now. As students, we worked hard and cared mostly about preparing for a good future. Among my friends and I, the “drug of choice” was an all nighter listening to one of Um Kulthum’s new songs, or to Nahida Fadli Dajani’s midnight radio show Museeqa Muntasaf al Layl. We saved to be able to go dancing all night to French, Italian, Spanish, English, American music at the “Caves” getting drunk mostly on coca cola!

But most importantly, growing up in the 60s in Lebanon as a woman was especially rewarding. Coming from a family of strong women starting with my great grandmother, it’s with pride that I look back at having had a free, equal, and assertive role in society.

I left Lebanon in 1969 never to go back and live, but on every visit as I stroll down Hamra Street, as I walk around the oval at AUB….. Oh to relive Beirut in the 60s!!!”

Nayla Sleiman, Atherton CA

“As my childhood home was on the Old Saida Road along the Green Line, war started early and overshadowed all my memories. I don’t even have any photos to remind me of places or people that I used to know, as everything was either destroyed or stolen. Although my memories are hazy, I remember the St. George and Bain Militaire where we used to go with our older cousins to swim during the summer. I also remember the mountain resorts of Aley and Bhamdoun where we ate tamryieh, the delicious semolina-filled fried pastry which was a specialty in those parts. We spent a good part of the summer break in Kayfoun, also in the mountains southeast of Beirut. As young kids we used to love roaming and exploring in the horsh or wooden areas, and so many times we would lose our way and end up in the nearby village of Shemlan. We depended on lovely villagers to show us the way back and quite often they turned out to be friends of our families. Lebanon was such a small place and it felt like everyone was somehow connected. Sometimes we would be sent to the furn or traditional bakery to make manakeesh, the famous Lebanese flat-bread covered with thyme and olive oil, and the best part was playing with the balls of dough before they were rolled out. I also still have vivid memories of Beirut’s old downtown, especially of the fountain in Bad Idriss and the nearby el Antableh juice shop where I used to love ordering the sweet syrupy Jellab and scooping out the pine nuts and raisins that floated in the drink.”

Rula Murtada, Brighton, England

Bill Tracy conducting the International College Glee Club in Beirut, where he was teaching in the early 1960s

I loved living there, not only sunning and swimming on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea and skiing in the close-by snow-capped mountains or hiking and picnicking in wooded river canyons, but also enjoying a surprisingly cosmopolitan city with outstanding educational and medical facilities. Happily, after high school and graduate studies there, I also had two very satisfying jobs in close succession. First I taught English in a private international high school with bright, enthusiastic students already fluent in French and Arabic. Then I worked as assistant editor of an English-language, Middle Eastern geographic and historic magazine with an international circulation.

Lebanon, with an ancient Greek, Roman, Crusader and Turkish past and a more-recent history as a post-WW1 French mandate, has Beirut as its capital. The city boasted of bustling markets and excellent restaurants and nightclubs, and a stream of international films, lectures and traveling theater. It had both a seaport and airport and was a convenient gateway by land to nearby Syria, Jordan and Palestine.

Most all I appreciated the Lebanese people. Muslim, Christian, Jewish and others, they were almost uniformly warm, out-going and friendly, generous and hospitable. Winter and summer, spring and fall, every day of my time there was a joy.”

Bill Tracy, USA

“In the summer months we moved to the mountains, to our hometown of Sofar. In the mornings my parents and grandparents sipped their Turkish coffee on the porch while us kids ran around. We lived at the end of a private road that led to nowhere, except our house. We had lots of land and had the run of the place.

Ghassan Hamdan standing in front of the now defunct railway station in his ancestral mountain village of Sofar in January 2017. The national railway was functional until the civil war.

There were three caves within 15 minutes from the house. They were quarries from the previous century which went on for several hundred meters underground. We used to take a tin bucket and put a candle in it so we could see in the pitch darkness. I could have brought a flashlight, but that wouldn’t have been fair because the village kids that I hung out with couldn’t afford one, and we were taught to be humble and not show off. But I did sneak one in to cheat when we played hide-and-seek. We gave names to different spots in the caves which became known to us as the crown, the throne, the prison, and the guard house. They were good days. I wanted to show the caves to my kids who were born and grew up in Louisiana, but they were bombed during Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon. The Israelis were worried that the tunnels would be used to stage attacks against their troops which were stationed in the mountains. One time, I had a fight with some gypsy kids who had come from a nearby encampment to take over our caves. As king of the trenches, I stood on the cliffs overlooking the tunnel entrance and started lobbing down rocks. One of them landed on a boy’s head and I could see the blood gushing out of the wound. The rest of his gang banded together and chased me up the hill. I ran as fast as a chubby boy could run and made it to our yard where my grandmother was making tomato paste on the open fire. She immediately saw the fear in my eyes and told me to get into the house. When the gypsy boys arrived, she told them that the boy they were looking for had passed her and run up the road. They had no reason to doubt this decent-looking old woman who had sent them on a wild goose chase.

I have such fond memories of rural life in Lebanon before the war. I wish I could go back in time with my kids, for just a brief moment, to show them what it was like to have the run of the place. Since that is not possible, at least not yet, all I could do is take them to the spot where the caves used to be and tell them the stories over and over again.”

Ghassan Hamdan, Shreveport LA

“Lebanese society was built on strong family ties, yet it was fragmented along class and sectarian lines. My mom came from a well off Sunni Muslim family and could have married rich, but instead she chose my father, a distant relative. Orphaned at age six, my father was forced to drop out of engineering school in Egypt when his scholarship ran out a year before graduation. To boost his moral, my mom encouraged him to enroll in law school after which they both established the Sinno Family Foundation to assist other students so that they would never have to drop out of school for lack of funds.

My parents were government employees because they strongly believed in being founding members of a newly-independent democratic Lebanon. As education topped their list of priorities, they enrolled us in French schools that provided excellent education. This is where I acquired the skills to navigate between cultures and the social mobility which led me to become the professional I am today.

Janine (L) with her family on a picnic in a forest near Hammana, a popular mountain resort east of Beirut.

However, the gains that I made from mixing with classmates who came from a more pampered background did not come without pain. While some classmates went on ski trips on the weekends, our family outings consisted of visiting aunts and uncles and occasionally making affordable nature trips that I enjoyed tremendously. I felt the class divide most severely in fifth grade when almost half the classroom emptied by the second week of December as well-to-do students were taken out of school early to travel to Paris for the holidays, while the rest of us stayed back, resentfully waiting for the official break.

As my parents became aware of my predicament, they started taking us on trips that they could afford. In 1971, we accompanied my mother on a business trip to Iraq. While she was flown there by the government, my father drove us all the way to Baghdad to meet up with her. However, the trip that had the greatest impact on me was a 1972 summer vacation to Paris. We traveled in a car convoy of twenty families who were on a mission to promote Lebanon as a tourist destination. The trip was the perfect opportunity to show off the true Lebanese spirit characterized by love of adventure, culture, and sharing good times regardless of sectarian divisions. The trip opened my eyes to the beauty of diversity and helped boost my confidence in making friends irrespective of class. It also taught me skills such as time management and respecting the rules of host countries. We visited museums, learned history and geography, and proudly distributed brochures about Lebanon. Some of the people we met became lifelong friends who checked on us in the early years of the war. Among those was a German man whom we met as a result of a fender bender. When we hit his car from behind, my dad came out to check the damage which was minimal. Instead of involving the police, the two men simply shook hands, exchanged addresses, and stayed in touch. This was a lesson in conflict resolution, positive connections, and friendship, all inherent characteristics of Lebanese-hood.

Yes, my parents borrowed money from the bank to make sure their four children and their cousin had that unforgettable experience, but this trip broadened my faith in humanity and gave me the resilience I needed for the hard years to come.”

Janine Sinno Janoudi, Okemos, MI

Samia standing between her parents after her Confirmation at the Catholic church in Antelias, during Lebanon’s Golden Age.

Facing the sea, our home was surrounded by orange and citrus groves and stood alongside a small river where I used to play with the neighbourhood children.

My grandparents lived nearby in a large stone house, where I spent most weekends and holidays. I loved the smell of the jasmine, gardenia, and fitna or frangipani trees in their garden. With my grandma. I used to make necklaces from the flowers that grew on those trees. Their house was also in the middle of an orchard of orange, citrus, mango and custard apple (or qashtah) trees, and next to a small vineyard where the grapes dangled. My grandparents’ neighbours raised chickens which gave us fresh eggs for breakfast. I often woke up to the sound of the rooster crowing in their garden.

Inside these groves is where I played with my neighbourhood friends all day climbing and swinging off the trees, playing hide and seek and tag, and treating ourselves to fruit delights including mangoes, custard apple, oranges, and tangerines. Up in the hills we could pick wild thyme or zaatar, and take it home to be ground up in the kitchen.

Spring in Antelias was divine, with the whiff of the orange blossoms, the balmy weather and Fairouz singing the Passion for Good Friday at the church of Antelias, from where her composer husband Assi originates. Good Friday, Palm Sunday and Easter Mass in Antelias are traditions that I have always cherished and these lovely memories have stayed with me pulling me back every year. Until today, I still head to Antelias, now accompanied by my children, to take part in the procession around the neighbourhood after Mass on Palm Sunday, when we hold up palms and Easter candles.

But Fairouz no longer prays there. The arrestingly beautiful orange groves in all their wildness, along with nearly all the old stone houses, have been bulldozed and supplanted by a jungle of concrete blocks, mega malls and restaurants. The orange blossoms are no more than a whiff from the past. The once crystal-clear sea in front of our house where we swam when we were children has become a dump for garbage and sewage.

The war, and the destructive habits it engendered, not only shattered our innocent childhoods but also the beautiful suburbs we grew up in.”

Samia Nakhoul, Beirut, Lebanon

“For a child under ten, holidays in pre-civil war Beirut meant a constant diet of cartoons in the late afternoon – a deliriously decadent experience for a boy raised on the BBC’s more instructive programming – as well as episodes of Bonanza, Rin Tin Tin, Kojak and of course Tarzan, the ultimate übermensch for the Lebanese male. There were also trips to Toyland on Hamra Street and Donald Duck near Raouche.

Beirut also meant American cars, American breakfast cereals (hands down better than anything in England); DC comics, Tintin and Asterix books in French; mini Chiclets and Canada Dry Sport Cola.

For a young boy dropped in from an English prep school it was a wonderland.

The swimming pool at the Hotel Phoenicia shortly after it opened. Phot. Jack P. Dadian

The Phoenicia Hotel was our home-away-from-home during this period. Like the St Georges, the Holiday Inn and the Cadmos, it received a bit of a pummelling during the 15-years of conflict, but it was lovingly refurbished in the late 90s and today, by and large, stands proudly faithful to the original design by American architect Edwatd Durell Stone. The main lobby on the first floor is in the same place, as is the adjacent pool area. But what has gone – and I really think the owners missed a trick here – is the bar on the ground floor that had a glass-backed wall, that allowed customers sipping their cocktails the voyeuristic treat of watching guests swimming in the pool above.

I was so fascinated by this that, in the hour or so after lunch when as kids we were told we had to wait for our food to digest before going back in the water in case we drowned, I would slip away and position my eight-year-old self at the bar, where I would nurse a 7Up and stare spellbound at this constant subaquatic drama.

I say you could see people “swimming,” but most of the time there wasn’t really much happening apart from a curious ballet of legs treading water. But every now then this rhythmic, and admittedly rather soporific, routine would be broken by the thrilling sight of a man diving down and swimming to the window and signalling to the barman for another round of drinks.

This was clearly the quickest, not to mention the smoothest and the most fun way to get things done, as long as you knew the barman and he knew your poison. But if you did, and they always seemed to know him, the order would be hastily prepared; put on a tray and given to one of the waist-coated and tarbouche-clad waiters who, with the clap of a hand, would be dispatched poolside with the precious resupply.

Looking back, it was marvelous stuff!”

Michael Karam, Brighton, England

“I was born in Beirut in 1961, a period when Lebanon was peaceful and considered the jewel of the Middle East.

We used to travel all over the country on weekends and holidays discovering its beauty. That is where I acquired my taste for travel and unquenchable thirst for open spaces and wild landscapes, which would launch me into a career in photography. As an early teen, I remember the colors that Lebanon offered: the deep blue of the Mediterranean in all seasons, the lush green hills where we picked cyclamens and wild flowers in spring, the heavy dark clouds that rolled off the coast in late fall, and the snowy mountains in winter. I remember the smell of the earth after a downpour and the fragrance of orange blossoms in spring.

Jack (2nd from R) with his brother Emilio, Sister Yolla and parents Gaby and Vivian at Khalde beach in 1970/71

We used to drive to the south along the coastal highway passing endless beach stretches in Khalde, south of Beirut, where we posed for family pictures. There were ancient roman ruins that had been there for centuries, but then they were transported elsewhere to make way to the runways of Beirut’s international airport. In Damour, a town further south, my father used to stop to purchase fresh produce. He was a good bargainer and managed to buy ten heads of salad for one Lebanese pound. He would fill the trunk of our blue Peugeot 404 with romaine salads, tomatoes, and fragrant oranges and clementines. Sometimes we would head in the other direction, north to Maameltein near Jounieh where we feasted on fresh fish – mainly grouper or red-mullet. Further north, I remember the silhouettes of workers as they harvested salt along the shoreline in Chekka, as well as the incredible varieties of Arab pastries in Tripoli.

My favorite destination was the village of Qartaba, north of Nahr Ibrahim, which we visited twice a year to have lunch at the Abu Nasr restaurant, owned by family friends. The road up was narrow and offered stunning views of river gorges and the surrounding mountains. The two attractions that this place held for me were the gazelles that grazed in the nearby fields, where I ran around, and the generous portions of home-made ice cream that I was allowed to consume at any time.

We spent our summers in Bois de Boulogne, a village near Bikfaya northeast of Beirut. The resort is famous for its pine forests, endemic to the Mediterranean, which provided a much welcome respite from the city heat. We spent our days in the wilderness riding our bicycles up and down dirt roads or playing football.

When I turned 13, the war suddenly broke out putting an end to those magnificent escapades. In 1975, my father’s factories were looted and burnt. Our mountain house faced a similar fate when Syrian troops entered the country. Lebanon spiraled into violence and destruction putting an end to those blissful days. However, those cherished memories remain vivid in my mind.”

Jack Dabaghian, Paris, France

Lina, her brother Danny, and their kitten Mickey. They are wearing the light blue “tabliers” that were part of the uniform at Collége Protestant Franҫais.

“The smell of autumn at the start of the school year brings back sweet memories of my childhood in Beirut. Preparations for “La Rentrée” took place just before the month of October. We would get fitted for our uniform in a small annex of the Collège Protestant Francais where seamstresses scurried around school children of all shapes and sizes. Girls were handed navy blue twin sets and the boys a crisp white shirt. Skirts and pants were then made to measure and the smell of new material marked the beginning of another academic year. The next stop was “les fournitures”, that quintessential French tradition of buying new books and notebooks. Our parents would spend a small fortune on these goodies. As we collected our matériel, we took a whiff of the new notebooks, the indescribable odor of factory-bound paper. We would then pick up a list of additional supplies and head to Bawarshi in Hamra. Upon entering the stationary, the smell of the new welcomed us in. As we proudly filled our “cartable,” we would get a momentary high sniffing the Elmer’s Glue which lasted until the inevitable comedown once school started.

Next stop was Hashem in Bab Idriss, the only shoe seller around at the time, where my mother would buy me and my brother our one and only pair of shoes for the year. I’d sniff those too, taking in that lovely smell of leather. I remember my mother’s beautifully manicured red nail pressing down on the front of the shoe to check and allow for growth through to the end of June.

Bus numero 10 with Monsieur Georges came by every morning to take us to school. We would head to the “casier” outside our class where we would don our “tablier,” the blue apron we wore to protect our uniform. The girls’ had a bow at the neck. They were beautiful uniforms, very classy and very Sixties, one for autumn and winter and another for spring and summer. We would join the whole school body in the immense hall of the school for “Culte,” to listen to our school director and sing beautiful hymns to usher in a new day. Those memorable twenty minutes united us regardless of nationality or creed.

After a few years going home for lunch, our parents opted for sending lunch to school with us. I was envious of those kids whose parents had signed them up for a meal at the “refectoires.” I can still remember the sweet smell of food wafting out of the cafeteria, in spite of my friends’ assurances to the contrary. My disappointment was often compounded by the discovery of ants that had crawled into my square metal colorful Disney lunch box and my hotdog. My classmates in turn envied me for having food sent from home. Luckily, I would have indulged in a “pain au chocolat” at “goûter” during the morning break, which consisted of a tablet of milk chocolate tucked into a mini-baguette.

Trips to the “Infirmerie” were de rigueur and I often feigned stomach aches to be sent there, always accompanied by a classmate. The smell of antiseptic drew us in, and the nurse administered a few drops of Rickles de Menthe (an alcohol-infused liquid) on a square of sugar. Just like horses, we delighted in this treat.

My sense of smell and taste evoke long forgotten memories. Wherever I am in the world, autumn makes me nostalgic for those early days of bliss, though the smell of wet earth following the first rains is never quite the same.”

Lina da Cruz Lamirande, Berkeley CA

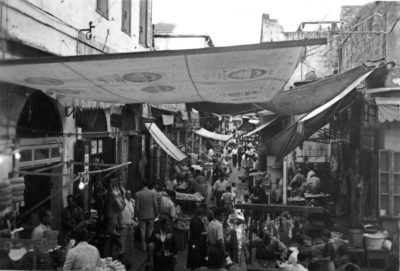

The old Souks in downtown Beirut before the civil war.

“The Atef Khodr shop in Souk El Joukh, the textile market, located in downtown Beirut between Allenby Street and Souq Al Tawileh, was a famous meeting point for our extended family, especially on Saturday mornings. My father, like many of his fellow shop owners at the time, was proud of his business which was not merely a trade, but also a lifestyle. The two long cream color tables, used to exhibit and cut fabrics, were transformed into coffee tables when special guests dropped in on Saturday mornings or in the late afternoon on weekdays. Atef, well known for his hospitality, ordered an assortment of traditional drinks including lemonade, jellab, and tamr hindi from the famous Berket Souk el Tawileh, and sometimes added sweets such as katayef and mehallabieh. He served his guests with love, a pleasant conversation, and always a big smile. For the children who tagged along with their moms on those frantic Saturday morning shopping sprees, the treat at Ammo Atef’s shop was special.

In spring and summer, my father closed his shop on Saturdays at 2.00 p.m., a time he awaited impatiently every week to head to his beloved hometown of Baakline, in the Chouf Mountains. As my father did not drive it was Antoine, our Coptic Egyptian driver, who picked us up from the shop in our 1958 Ford Ferlane. Often many cousins, young children and adolescents, would be waiting for Ammo Atef to finish his work and take them to Baakline. Our grandparents, aunts, and uncles would be anxiously waiting, and we would spend the weekend surrounded with their love and pampering. My father’s shop was full of happiness, not only fabrics.

Atef loved his shop which was his life, not only economically but also socially. He had many friends in the souk, most of them Armenians. One of his closest colleagues and friend was an Armenian tailor called Joseph. During the war, Joseph sought refuge in Baakline where he tried to restart the business with my father. One day he insisted on going to Beirut, against my father’s advice, to check on his family. We never saw him again. Lebanon’s war ripped families apart and many never recovered.

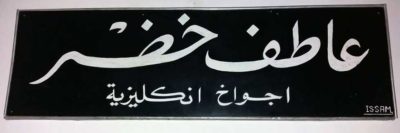

The original sign that once was above the shop door reads: “Atef Khodr British Wools”

One year before the war erupted in April 1975, my father decided to redesign his shop. One of the best interior designers in Beirut advised him to use oak wood, so the cream color tables gave way to oak wood tables and the floors were redone giving the shop a new look. My father had to take a loan to cover the cost, and, like many honest traders at that time, his cash was in his merchandise. His shop was ready to receive all the Dormeuil, Emmanuel Zegna and other brands imported from England. Atef was proud that he never bought two identical pieces to ensure his customers exclusivity. When the war broke out, my father had fabrics at the port, and some were still waiting to be loaded off ships. Many never made it to his shop. As the fighting started in the souks, my father was advised to empty his shop, so he took all the fabrics to Baakline. He also had a safe in his shop, where extended family members and friends kept valuables as Atef was trusted by everyone. Luckily, he emptied the safe just in time before it was blown up by the militiamen who destroyed his shop.

What remains of my father’s shop today is the sign that was on top of the door. My nephew, also called Atef, keeps it in his bedroom. One day perhaps, it will go up again. Beautiful memories of a loving father and a warm uncle to a dozen young cousins who are now old….that is what remains of the Atef Khodr shop in Souq Al Joukh.”

Adele Khodr, Kabul, Afghanistan

If you have a memory of Lebanon’s “Golden Age” you want to share please send it to: nschiller@photorientalist.org

The end of Lebanon’s Liberal model? – 128 Lebanon

[…] market, and minimal government interference, made Lebanon a unique place in the Middle East. In its golden age, from the early 1960s till 1975 Lebanon became a glitzy tourist attraction, the mecca of the […]

EXPLAINER: The Islamic world was urbane, secular and in some cases democratic. What happened? - Secular Underground Network

[…] films were popular. The whole Arab world was like this too. Beirut in Lebanon was even called the Paris of the Middle East. Nasser died in 1970 of a heart attack. His successor, Anwar Sadat, may have been of a similar mind […]