by Barry Iverson

A 1928 family portrait showing Van Leo (L) his brother Angelo (C) and sister Alice (R). AUC Collection, Phot. Varjabedian

Van Leo, born Levon Boyodjian, elevated portrait photography to new heights by creating imagery that accentuated his subjects’ features through manipulation of lights and shadows. Inspired by postcards of Hollywood movie stars, it was no surprise that he became the photographer of choice for entertainers, the elite, and those seeking an artistic portrait for posterity. His work also included an extensive collection of world-class self-portraits. In spite of ups and downs in his career, which resulted from changes in Egyptian politics and society and the commercialization of photography, Van Leo strove to maintain high standards and stay faithful to his art. His career ended on a high note when his work was recognized and chosen for preservation at the American University in Cairo.

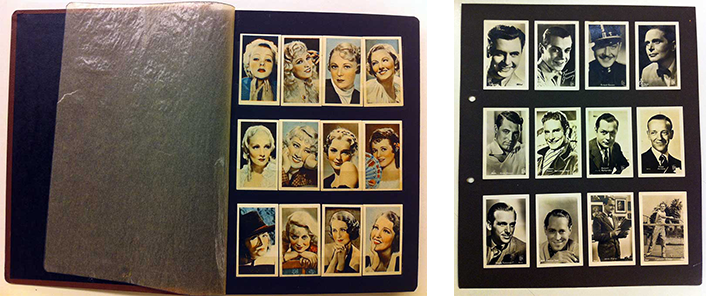

Van Leo’s passion for portrait photography can be traced back to his teenage years, when he was a student at the English Mission College in Cairo’s suburb of Heliopolis. At age 16, he was bored with school work and more interested in sports; however, what the young man became fascinated with was Hollywood postcards which he began collecting. He was drawn to the dramatic side lighting that produced deep shadows, the careful positioning of the hands, the well-chosen props, and the backgrounds, all of which he would later incorporate into his own work.

Van Leo’s collection of Hollywood stars that inspired him to become a photographer. AUC Collection.

After completing his secondary studies in 1939, Van Leo enrolled at the American University in Cairo, only to withdraw a year later and resume an apprenticeship at Venus Studios, which he had started the previous summer. By then, he had realized that his future was in photography, which was becoming a lucrative business in Egypt due to the influx of foreigners at the start of World War II. Cairo and Alexandria, which already had sizable communities of foreign residents, were flooded with newcomers from destinations such as England, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, the United States, India, and Sudan, creating a great demand for skilled photographers. The studio owner, Arakel Artinian, was a classical photographer who neither deviated from three-quarter body length poses, nor experimented with the bold lighting and shading techniques that fascinated Van Leo. Nevertheless, his business was booming due to the rising demand.

Even though Van Leo took most of the photographs, Angelo’s name appeared on all the images. Patrick Godeau Collection

Artinian was fond of Van Leo and saw great potential in him, which perhaps motivated him to relegate his young apprentice to routine tasks as opposed to taking him under his wing and teaching him the secrets of the trade. After three months, Van Leo realized that his training at Venus Studio was worthless, and quit. He had been encouraged to start his own business by a British officer named Paul Hands, who had visited the studio and taken notice of Leon’s talent. The young photographer was optimistic about his prospects, but he needed help. He therefore approached his older brother Angelo, who was then employed by the British Army, and they decided to start a joint venture. In January 1941, they opened a studio in their parents’ living room. To help his sons launch their business, Alexander Boyadjian offered some of the equipment including the mammoth 10×10 inch large format camera, which would remain Van Leo’s primary camera until he retired in 1998.

Allied soldiers were Angelo and Van Leo’s first clients. Phot. (L) Patrick Godeau Collection, (R) AUC Collection

When the studio opened, Hands was the first client, but he was soon followed by a flood of soldiers, officers, and members of the high society. However, it was the entertainers who meshed best with the brothers and together they painted the town red frequenting Cairo’s glamorous night spots, most notably the Arizona Nightclub on Pyramids Road. The brothers’ studio would soon become a legend. However, the honeymoon came to an end in 1947 when Van Leo decided to break from his brother. The reasons for the break up were economic, but there were deeper tensions. Business had become sparse when the war ended in 1945 putting strain on the establishment. However, the greater tension resulted from Van Leo’s resentment of his older brother. Angelo, who was four years older, had little knowledge of photography when he entered the partnership and it was Van Leo who taught him everything he knew. Nonetheless, it was Angelo’s signature that appeared on all the prints, including artists’ pictures supplied for free to the opera house and theaters for their brochures. It wasn’t until the last year of the partnership that both brothers signed side-by-side. Van Leo realized that he was the more talented of the two and needed to break off on his own. Any chance he got, he would criticize this brother’s abilities. Commenting on a portrait Angelo shot of him in Paris in 1975, Van Leo stated, “Angelo made one mistake – my nose is big. He should have turned me one centimeter to the left…he is not an artist like me.”

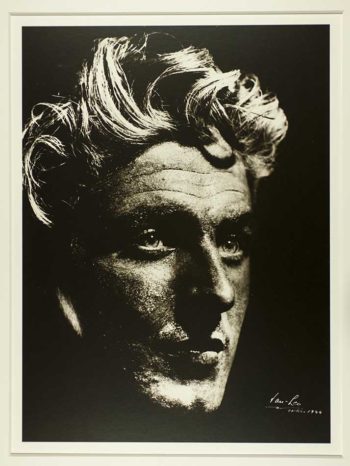

Van Leo’s early masterpiece of the South African Teddy Lane. Norbert Schiller Collection

Despite the frictions, Van Leo produced some of his best work while he and Angelo were together. His iconic portrait of South African entertainer Teddy Lane taken in 1944, showed how he built on his fascination with the Hollywood stills to create his own signature style. Taking notice of Lane’s distinct features and facial structure, the photographer decided to apply Vaseline to the cheeks and forehead, and place a black velvet cloth behind his head to completely darken the background and accentuate the face, blond hair, and blue eyes. “You must profit when you see such beauty. You must also make some pictures for yourself, from your inspiration, not just what the client wants,” Van Leo would say. That was the secret to his best work, including this haunting portrait.

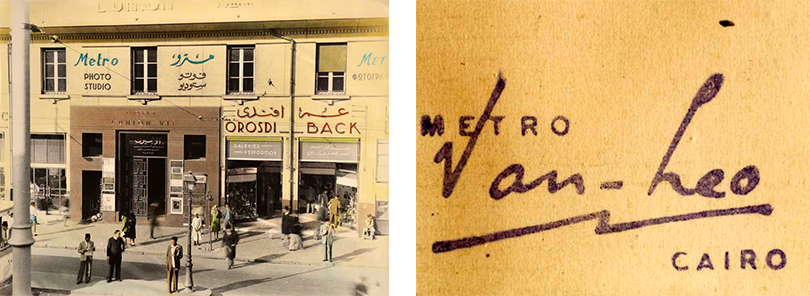

In 1947, after the split, Van Leo purchased the portrait studio “Metro” at 7 Avenue Fouad in downtown Cairo, where he worked until the end of his professional life. When he adopted the artistic name of Van Leo, a play on words on his name Levon, he changed the studio name to match his new name. He had finally achieved independence, fulfilling his father’s dream. Alexander had to clock in at Eastern Tobacco every day at exactly 8:00 a.m. which is something he did not wish for his children. While still establishing himself, Van Leo took portraits of performers for free, in return for having the studio name displayed prominently on images used for productions. One of his early customers was super star Rushdy Abaza, who at the time was an aspiring actor with a day job at the Union-Vie French insurance company, located in Van Leo’s building. In need of a portfolio to show directors, Abaza went to Van Leo to have his portrait taken. This picture was Abaza’s ticket to his first minor roles, and when he became a big shot he never forgot the photographer who catapulted him to fame. Abaza spread the word and Van Leo became the entertainment industry’s favorite photographer.

After separating from Angelo, Van Leo took over Metro Photo Studio but kept the name until he became known. Phot. (L) AUC Collection, Van Leo, (R) Norbert Schiller Collection

During the first decade after the 1952 Revolution that brought Gamal Abdel Nasser and the military class to power, Van Leo managed to keep his business afloat. However, following the exodus of foreigners in the 1960s and 70s, his clientele largely dried out. Out of necessity, the art photographer had to resort to taking passport pictures, and wedding and family portraits. Babies were not his favorite subjects as they urinated on the props and made him nervous. During these lean years, he shot most of his pictures in 35mm film, as he did not want to use up expensive sheet film or 6×6 roll film on subjects who were of little interest to him.

Although he had to respond to market demands to survive, Van Leo was never motivated by money. His true passion was his art as announced on his business card, which read, “Van Leo-Art Photographer.” He was a stoic who forged his own way by working hard and doing everything himself. He had no secretary to usher in clients, no accountant to maintain the books, no lab assistant to process his film, and not even a studio assistant to change light positions, or lift his heavy wooden studio camera. Unlike other studio owners, Van Leo did not keep his door open to attract business. Clients had to either ring the bell or call for appointments.

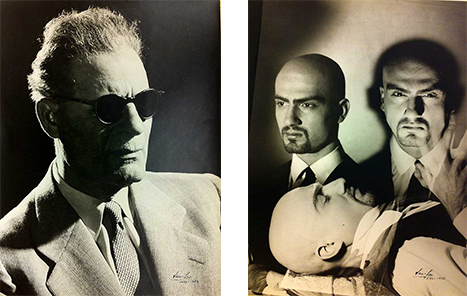

Iconic Van Leo photographs of Egyptian writer and intellectual Taha Hussein (L) and self-portrait (montage) titled “No Escape from Death.” AUC Collection.

It was by following these austere work ethics that Van Leo created his gigantic portfolio of hundreds of thousands of images, most of which were portraits. “Faces…most of those entering the studio are not interesting faces… I always liked to photograph theatrical people more…but ordinary employees…they sit there like statues,” he said of his clients. Van Leo acknowledged that he produced his best work when the customer gave him full control over the photo shoot. The best example of a trusting and cooperative client was Taha Hussein, one of Egypt’s most famous writers who was also blind. “The inspiration was from my heart: – I saw the dark eyeglasses, and I already understood that he was a famous personality. I started to play to with the lights, and it came out like this one.” This was the best portrait ever taken of Hussein and to Egyptians that picture with the heavy shades of black and moody tones, represents everything they know about their beloved writer.

One of the main keys to Van Leo’s success was his ability to connect with his subjects and make them look glamorous regardless of their physique. If the subjects were old, he would take them at a slight distance, usually at a three-quarters view and neatly position their hands. At such a distance wrinkles, blemishes, and age spots were less prominent. In spite of his ability to capture his subjects at their best, Van Leo’s most celebrated works are ultimately his self-portraits of which he took a staggering 300-400. Driven by curiosity and vanity, the best of his introspective work was done between 1942 and 1944, while he was still young and good-looking. He explored existential topics including his own death in the montage titled “No Escape from Death.” These self-studies also show a more playful side of his personality as in many of the images he took on different identities including that of Jesus, a beggar, a woman, a WWII pilot, a cowboy, a robber, and a Saudi Sheikh. For these images, he did not spare any expense using 18×24 cm sheet film, which Alexander described as a foolish splurge. Nevertheless, the self-indulgence was well worth the price as it resulted in a unique collection of self-portraits, which may be unrivaled in the photo world at large.

Van Leo mastered lighting to enhance the sensuality of the female body. Phot. (L) AUC Collection, (R) Norbert Schiller Collection

Van Leo also had a considerable collection of nudes where he explored sensuality and the female body using his trademark Hollywood style lighting. However, in the 1980s, as Egyptian society became more religiously conservative following President Anwar Sadat’s assassination, the photographer destroyed much of the negatives and prints in this collection by burning them in his oven, out of fear that they would fall into the wrong hands.

The 1980s were a turning point for Egypt and Van Leo in more than one way. It was then that color was introduced to the country, which was a few steps behind the international trend due to economic reasons. This change in the medium tormented Van Leo, who as a purist saw black and white as the only possible means of artistic expression. While other photographers and the public at large embraced this revolution, Van Leo resisted it only caving in at his clients’ request. His reluctance was evident in his work which shows a decline in output and quality during that period. No longer feeling inspired by his work or subjects, Van Leo let his clients take control during photo shoots, which was a recipe for mediocrity for a master like him. Luckily, he bounced back in the 1990s when he was rediscovered mainly by tourists and foreign residents seeking retro portraits. He resumed his beloved art form and, in a sense, came back full circle from his heydays in the 1940s and 50s. There was also renewed demand for this classic prints of Taha Hussein, Omar Sherif, Dalida and others which he sold to stay afloat. However, he turned down every offer to purchase his entire life’s work and was adamant about keeping his archive as a complete collection housed somewhere in Egypt.

On January 24, 1998 Van Leo took his last portrait, which was of my wife Nihal and me. When we went to pick up the proofs, we realized that he could no longer raise the mammoth large-format enlarger as he had done for 57 years. I tried to devise a counter-weight to ease the burden, but it did not work. Van Leo then sadly realized that the disks in his back had become too aggravated, and that he no longer had the physical ability to continue working. He announced the closure of the studio marking the end of an era.

The last photo Van Leo made was of Barry Iverson and his wife Nihal in January 1998. Van Leo beside his faithful camera in 1996. Phot. (L) Barry Iverson Collection, (R) Josef Polleross

In April 1998, Van Leo donated his entire archive to AUC, a grand gesture motivated by passion. The fact that he had attended AUC in 1940-41 played no small part in this decision. However, Van Leo did not want his images to become museum pieces; he wanted them to be accessible to the public. He therefore encouraged me to make prints, but remained picky about quality. He was able to sign about one hundred prints before he died.

In March 2002, Van Leo passed away from a heart attack at his apartment in Cairo. His servant Ahmed called me in a panic, but when I arrived it was too late. He was buried the next day at the Armenian Cemetery in Cairo.

In 1944, Van Leo visited an Armenian fortune-teller who told him that he had a good heart and predicted that he would find what he wished for in life. He would become a great photographer, travel widely, and create work, which would be recognized by a museum. AUC has acknowledged his greatness, and as custodian of the Van Leo collection, is fulfilling his dream of having his legacy honored.

This text was edited and abridged by Zina Hemady. Iverson’s full-length biography is titled “The Life of Cairo Master Photographer Van Leo.” (ISBN 977–424-350–1)

Hello

I would like to buy a copy of the book ‘The Life of Cairo Master Photographer Van Leo’ (ISBN 977–424-350–1). Can you direct me to where I can find it?

Thanks

Եգիպտոսի լուսանկարչության հայ դեմքը | Aliq Media Armenia

[…] մեկը համարվող Լեոյին լուսանկարչության մասնագիտական կայքերն ու եգիպտական մամուլը ներկայացրել են իբրեւ «լեգենդ», […]

Van Leo: Architect of Old Egyptian Glamour Photography - Nathra Mostaqbaliyya

[…] was known to occasionally close his studio for extended periods to capture himself in various costumes, a […]

Van Leo: Architect of Previous Egyptian Glamour Pictures - Drimble World News

[…] was recognized to sometimes shut his studio for prolonged durations to seize himself in numerous costumes, a […]